top of page

Blaze Masters

Educational Forest Management Simulator developed in collaboration with Utah Department of Forestry, Fire, and State Lands

Contributions

-

Served as Scrum Master and utilized Trello to keep the 5 person team on pace

-

Led project pitch and One-Sheet design, coordinated with forest management agencies for consultation, led research for educational aspects of the game

-

Mediated an intense conflict within the team and persuaded all parties to commit to a unified team effort

-

Co-designed and iterated on Survey, Cut, Plant, and Extinguish mechanics

-

Pitched in with QA, Audio, and Writing efforts

-

Tools: Unity, Github, Trello

-

Platforms: PC, iOS

-

Team: 5 people

Cody Cottrell

Game Designer

"All fine architectural values are human values, else not valuable."

~ Frank Lloyd Wright

Level Design Process

1.) Know your mechanics

-

You can't design engaging play spaces without knowing what players will be doing in those spaces and the metrics associated with their play verbs. A testing gym is a great place to get a sense for how different mechanics feel in different spaces.

-

Here are some examples of mechanics and systems I've designed or prototyped myself:

2.) Collaborative setting research

-

If a level is going to contribute to a cohesive narrative and elicit deliberate feelings in the player, then it needs to not only respect the setting constraints established by the Narrative team, but celebrate them. Furthermore, the more projects I've been a part of, the more I've learned that it is absolutely critical to share that effort with an Environment Artist. LDs and EAs each have our own unique perspectives and if we're not consciously marrying those viewpoints and bouncing ideas off of each other, then the different ways that we see play spaces are all too likely to clash.

-

Personally, I find that researching the real world processes and activities that take place in different environments can help lay the groundwork for intuitive flow, memorable hero props, and even diegetic puzzle scenarios. Once you understand the function of a space, then mood boards can be a fantastic way to discover the architecture, shape language, spacing, color palate, and lighting that evoke the story's desired atmosphere.

-

Here are some examples of boards that have helped me to get my creative juices flowing:

Abandoned Soviet mines

Hungarian ruin pubs

Battle medic

Abandoned Soviet mines

1/3

3.) Paper prototyping

-

If you're not visualizing objective flow, sightlines, mood-mapping, and key gameplay interactions on paper or in collaborative software like Miro before you even open the game engine, then you're committing a cardinal sin in my book. Techniques like "molecule maps" can challenge assumptions about how player pathing can be arranged in more interesting ways, and a good piece of graph paper can highlight the need for consistent metrics, but the most important reason to buy into paper prototyping is that it is the fastest and cheapest way to ideate and iterate. Paper prototypes force me to imagine play spaces from a beat-by-beat perspective and inevitably discover issues that would have taken much more time to solve if I'd stumbled upon them in-engine.

-

I also think it's important to call out that your first idea is rarely your best idea. I try to use this phase to rapidly develop at least three different options to pitch to my core team from the very start. I also try to keep a "low scope" and "high scope" version of any pitch in mind from the beginning so that my designs aren't critically compromised if down-scoping is required down the line.

-

Here are some examples of what a rough draft means to me:

Luxury night club

Soviet labor camp

Wavelength traversal

Luxury night club

1/3

4.) Layout presentation

-

Once I've got a firm idea of what version 1.0 looks like, it becomes vital to document it in an easy to understand, visually legible layout using a program like Photoshop or Dungeondraft. The reason why presenting a clear layout to the team is so important is because it saves a lot of in-engine iterations by bringing other domains into the collaborative process while changes are still cheap. In fact, I find that it's often worthwhile to make separate versions of the map with specific callouts and Confluence hyperlinks for each discipline so that they don't get overloaded by information that's not relevant to their responsibilities. Constructive feedback from another set of eyeballs is the life-blood of game development!

-

I also think it's worth noting that I've been on projects that aim to perfect designs on paper as well as projects that dive in-engine without a coherent plan. In my estimation, the goal ought to be to use paper to get the entire team aligned on the vision for a level's moment to moment user experience and then get into blockouts as fast as possible since people just perceive things differently in 3D. In fact, there are some cases, particularly in levels with complex layers of verticality, where I think a very simple, color-coded cube collage in-engine is a far more efficient means of visualizing an environment to the rest of the team than futzing around with multi-layered 2D maps. The deliverable for this stage is ultimately team-wide clarity of vision with a strong metric-conscious starting point to build from.

-

Here are some example 2D maps that I've used to secure team-wide buy-in:

Sword of Atlas level 5 layout

Sword of Atlas level 1 layout

Sword of Atlas level 3 layout

Sword of Atlas level 5 layout

1/3

5.) Blockout/greybox/whitebox/blockmesh

-

Once the layout is set, it's time to bring it to life in-engine as rapidly as possible, working closely with an Environment Artist when possible to ensure that their goals are being supported in the very foundation of the level. It doesn't have to be pretty at first, but I believe it does have to accurately represent the physical and emotional feel of the space. Placeholder SFX and lighting can go a long way in establishing atmosphere. This is the first opportunity to test how it actually feels to inhabit and interact with the level and I've found that it's important to do this in a group setting, as a laundry-list of revisions inevitably get generated from something as basic as walkthrough through the environment.

-

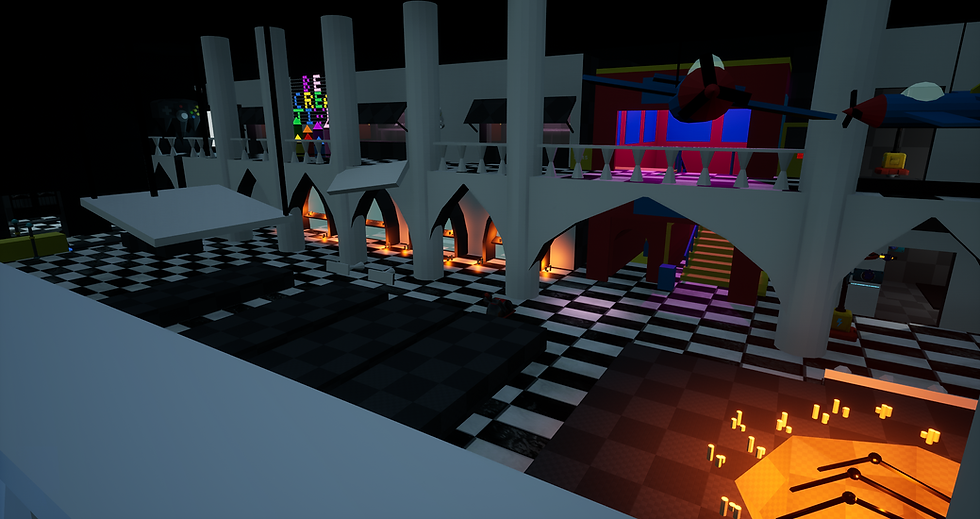

Here are some 1st iteration blockouts I've made that invigorated my teams with the passion and drive that come with clarity of vision:

1st Sword of Atlas blockout

Toy Store blockout

Shadow Soul courtyard blockout

1st Sword of Atlas blockout

1/3

6.) Iteration

-

Every iteration of a play space makes it incrementally better. It takes many, many iterations to get to something good. The more frequently a team can playtest, even with hacked together proxy functionality, the better the end product will be. As development moves along, it's important to conduct regular playtests to help find the fun, find the pain points, and balance encounters as well as possible. It's also important to stay agile as creative shifts, scope shifts, and technical hurdles demand new solutions; documentation must be updated as those new solutions are implemented.

-

One of my creative directors once told me that game development is 10% "great idea" and 90% figuring out why your idea actually isn't great. In other words, iterating on an idea and finding every flaw and complication and happy accidental detour is what actually makes a game great.

7.) Polish

-

As the flow of a level takes consistent shape and its layout locks into place, it becomes even more important to work closely with Environment Artists and Lighting Artists to set-dress and populate play areas without adversely affecting gameplay. The finished product never really feels finished, but if my work tells a story and absorbs players into the game-world while driving specific game behavior, I feel like I've done my job.

The Arious Estate - Sword of Atlas

Beldam's Hideout - Sword of Atlas

Corrupted Outpost - Sword of Atlas

The Arious Estate - Sword of Atlas

1/3

Keys to Success

Scripting

Iteration

Collaboration

bottom of page